Corpus-et-Vulnus is a project in a broad “performative” sense, naturally complex because it is made up of many paths that at times reconnect with each other. The many paths are the exhibited works, the author’s accompanying reflections, the references to the past and the present – Tàpies, Kiefer, Parmiggiani – and last but not least, the exhibition space where everything happens and regenerates through those who traverse the exhibition space. But it is also complex because it is aware of the functional limits that the works have as a symbolic language in relation to the fluidity of processes that concern and involve us. Bodies, as Jean-Luc Nancy wrote in “Corpus,” “are always on the point of departing, on the verge of movement, of falling, of moving away…” meaning they are not forms to be fixed like stable architectures, or in the sense of classical physics, substantial particles, but states of potential and relative movements. In other words, bodies inhabit, and places are influenced by their inhabitants. The “device,” a term that often recurs in Sergio Mario Illuminato’s reflections, is a mechanism made up of multiple parts related to each other, not so much in a mechanistic and formal sense, the result of compositions and measurements, but parts that hybridize for continuity. The device, a complex organism, is thus at the basis of a feeling that filters through the various elements: works and place. Everything is closely interconnected, to the extent that the thought (perhaps one should say the spirit) circulating among the various media (paintings, text, place) is the true device without a definitive form, just as the life that “corpus” and “vulnus” are made of is raw material. From this relationship arises the idea of an exhibition path as well as the path of thought that precedes and inhabits it. That “a good painter is inwardly full of figures” was a reflection by Albrecht Dürer, quoted by Salvatore Settis as an epigraph for one of his texts in the catalog of Anselm Kiefer’s exhibition at the Palazzo Ducale in Venice in 2022. Kiefer too claimed to think in images, aided by poetry. Trying to thin out the clouds, inherent in metaphors, and converging different media is typical of the post-media nature of contemporary perception, even when it comes to painting-painting, as in the case of “Corpus-et-Vulnus.” However, it’s painting that needs to nourish itself beyond the frame of composition, inhabiting a strong, site-sensitive place like the former Pontifical prison of Velletri, in order to place “the most fragile condition of human reality at the center,” as the author writes, shaping a thought-matrix of processes, like Nancy’s, to engage in a regenerative dialogue that begins in the exhibition moment. For this reason, one can also speak of a “performative” sensitivity beyond the narrow grammar of languages, because artworks can also function as performers in a field of activated relationships. We have been accustomed to internalizing painting as an unfathomable and self-sufficient sacred reality, to be looked at from afar, as if it were an island where one cannot land. While “watching painting – as William J.T. Mitchell argues in his Pictorial Turn – is watching touching, watching the artist’s gestures, which is why – Mitchell deduces – it is so strictly prohibited to touch the canvases.” Instead, working on the exhibition as if it were a biographical account that positions the author in a problematic field of relationships is a way of unveiling the work, making its process and vitality felt. Visual media do not exist, Mitchell further claims, wanting to argue that there are no “pure” media, as our senses cannot act autonomously, since we are within a body-organism. Corpus-et-Vulnus form a sentient and communicative organism whose signs are certainly not abstract illustrations of concepts, but rather the concepts-matrix themselves, as constituent parts of a living and proliferating organism.

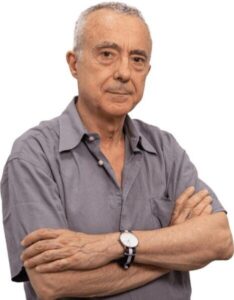

Prof. Franco Speroni, writer, historian, and art critic, professor of contemporary art history and history and methodology of art criticism at the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome